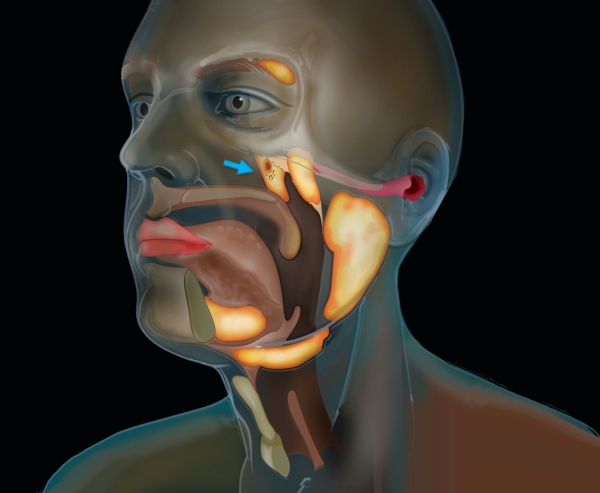

Researchers at the Netherlands Cancer Institute in Amsterdam have discovered set of salivary glands in the upper part of the throat. This can pave way for techniques that could improve the quality of life for people who receive radiation therapy for cancers of the head and neck.

The new glands have been labelled as tubarial salivary glands because these are situated over a piece of cartilage called the torus tubarius. The discovery was accidental since the researchers were studying prostate cancer.

The new set is about 1.5 inches on average and lie in the nasopharyngeal region, behind the nose and above the throat.

Radiation oncologist Wouter Vogel and oral and maxillofacial surgeon Matthijs Valstar were studying a new type of scan as part of their research when two unexpected areas lit up all the way in the back of the nasopharynx, which looked similar to known major salivary glands.

“People have three sets of large salivary glands, but not there,” Vogel explains. “As far as we knew, the only salivary or mucous glands in the nasopharynx are microscopically small, and up to 1,000 are evenly spread out throughout the mucosa. So, imagine our surprise when we found these.”

In collaboration with their colleagues at UMC Utrecht, they discovered that all 100 people whose scans they studied had a set of these glands. These patients had a new type of scan done for prostate cancer treatment, called PSMA PET/CT scanning. Show up clearly on this kind of imaging.

The researchers said in their report that sparing these in radiotherapy could help reduce the difficulty in salivation and swallowing that patients of head and neck cancer experience after radiation therapy.

“The human body contains a pair of previously overlooked and clinically relevant macroscopic salivary gland locations, for which we propose the name tubarial glands. Sparing these in patients receiving radiation therapy (RT) may provide an opportunity to improve their quality of life,” the researchers wrote in the paper published in the open access journal, Radiotherapy and Oncology.

More research is likely needed to confirm that these are indeed a new major set of salivary glands, and if confirmed, it would be the first discovery of new salivary glands in about 300 years, according to a report in Science. “For most patients, it should technically be possible to avoid delivering radiation to this newly discovered location of the salivary gland system in the same way we try to spare known glands,” Vogel concludes. “Our next step is to find out how we can best spare these and in which patients. If we can do this, patients may experience less side effects which will benefit their overall quality of life after treatment.”